There are some things that definitely are DnB, and there’s some things that are not.

An acoustic style that mimics an electronic style.

A live style that mimics a pre-recorded style.

A human style that mimics a machine-driven style.

Most electronica (electronic music, DnB, techno, jungle, etc.) is created by people who have little to no knowledge of the principles of music theory, and do not play an instrument. For these people, the programmers, the computer is the instrument by which they make music. So, for the most part, drummers do not create the drumbeats found in electronica.

The exciting thing about this is that if you analyse electronica beats, you will find a whole new vocabulary of beats never played before; they just didn’t exist. And this is the biggest reason that I can find for why this style is not based on conventional drumset rudiments – the programmers that created the beats didn’t know about them.

One advantage that programmers have over many drummers is that they have the opportunity to really analyse the beats they create. They have both a strong visual and auditory connection with the beats they create; they can hear and see them. This gives programmers a higher level of understanding of what makes a certain beat tick. It also gives programmers a particular advantage compared to drummers who do not read music. That is, if you have a graphic conception of a beat, you have an opportunity to really be objective in answering questions like, “Why does this beat feel unbalanced?” or “How can I make this beat more symmetrical?”.

A source of new sounds for the acoustic drumset.

A programmer can create infinitely more sounds on a computer than he or she can on a drumset. So, in order to bring the conventional drumset up to speed with electronica, a lot of new products have been introduced lately: small snares, special effects cymbals, and a lot of toys. By all means, go nuts! But think about these two issues before you buy:

- How many different sounds can I pull from this single piece of equipment?

- Can I use it for other styles of music I play?

A balance between independence and interdependence.

Drum n’ bass beats display independence in that the musical ideas played by each limb are not necessarily related. When you hear a DnB song, your ear may often latch on to just one (of many) repeating lines. In this way, much of what the audience hears in DnB is horizontal. Programmers are able to create electronica in a similar horizontal fashion – they will continually stack layer upon layer of beats as the song progresses. The music is continually flowing, and the groove is never interrupted. And incidentally, these layers can appear at very different tempos – synthesized strings at 40 bpm, a bass line at 80 bpm, a melody line at 160 bpm, a barely audible click at 320 bpm.

Likewise, there are four different layers in a DnB drumbeat. These layers will be referred to throughout the book.

Drum n’ bass beats display interdependence in that, in order to handle the fast tempos of electronica music, your body must be comfortable with new vertical combinations of limbs. Another way that programmers create electronica songs is to take vertical (cross-sectional) chunks of a different song and paste them back together in different ways. For example, if you label each vertical chunk of a beat, a programmer could easily take this beat….

…and change it around to this beat…

…or this beat:

Some of the more advanced beats in this book have different limbs playing different tempos at the same time. In order to pull this off, your limbs need to depend on each other like never before. Plus, your body must be comfortable with not playing certain limbs for extended periods of time.

A review: In musical terms, when this book talks about looking at a beat vertically, it means to look at the beat by each quarter note’s worth of time. When it talks about horizontal, it means to look at each of the four different layers (bass drum, snare drum, ride, and ghost notes) separately.

A style that is closely related to Latin drumset drumming.

The method behind recreating the feel of electronica is much like playing Latin or Afro-Cuban drumbeats. In these specific musical forms, 99% of the time there is an underlying, predetermined pulse that the drummer can mimic. Or, by not mimicking the pulse, the drummer can create a natural counterpoint. For example, a bossa nova.

The bossa nova pulse is set in stone. When a band plays a bossa nova, everyone “hears” the beat, whether the drummer is specifically playing it or not: where the cross-stick falls, the bass drum pulse, etc. A drummer can stray from the basic bossa to open his part up, and then return to it during someone else’s solo. The switching back and forth between complex vs. simple, extra-bossa vs. regular bossa, creates the feeling of tension and release that is essential in all forms of music. A bossa, or any other type of beat, would be pretty boring for both the player and the listener if it was strictly adhered to, especially in its most traditional form. Mix it up, for everybody’s sake, but be able to confidently return to the original beat when you need to.

The same tension/release approach should be taken with DnB. In order to effectively communicate with the band and the listener, a predetermined “pulse” should be chosen. Then, on top of that, the drummer can stray from it, and return to it. Back and forth. Tension and release.

The following is an example of a pulse. It’s just a simple riff, but play it until it’s burned into your head. It’s a very common DnB beat.

The pulse can also be played in the ride pattern.

When playing drumset in a Latin style, the drummer is mimicking the sounds and patterns of Latin songs that are usually played on other instruments. Patterns of bells, timbales, congas, and bongos are all imitated and approximated by bells of cymbals, toms/tom rims, and bass drums, all simultaneously by a single player. Drum n’ bass drumming does the same type of thing. A drummer’s ride cymbal can replace anything that is heard in a DnB song: a burst of static, or the sound of a tin can.

So if you know anything about Latin drumset beats, you are already ahead of the game. To review: Latin and drum n’ bass drumming both…

- Give the conventional drumset new sounds to play around with: sounds you can buy, and new ways to play your existing drums.

- Are identified with fast, consistent beats that rarely disrupt the clave. (Check out any book on Latin beats if you don’t know this term.)

- Are never played behind the beat. The pulse is always driving forward, not pulling back.

A balance between analysis and practice.

As stated earlier, most programmers are not drummers, and do not spend time practicing the beats that they create. They do, however, spend time analysing the beats that they create. This is so, in part, because programmers can see the beat displayed on the computer screen as well as hear the beat. To a programmer, the visual aspect of the beat is often as important as the auditory aspect of a beat. That is, a beat that looks appealing (like a beat that is symmetrical, or one that sounds the same played forward or backward) can be just as cool as one that sounds appealing.

Programmers understand their beats inside and out, vertically and horizontally. They know what each layer sounds like when it is played just by itself. So, in this respect, programmers have an advantage over drummers – they have a great conceptual and analytical understanding of their beats. The time spent analysing their beats gives programmers a great ability to choose the perfect complementary beat for a given song.

How do these changes in the music world apply to you, the reader of this book? First, it puts more pressure on you to be able to read music. Graphic representations of music, whether they are on a standardized notated staff or sound waves on a computer screen, are increasingly becoming a more common way for musicians to communicate with each other. Being able to read music is a necessary step to being able to communicate with other musicians.

Second, in today’s music world, just practicing a beat is not enough to gain a full working knowledge of it. I’ve found that if you analyse a beat on paper, you will more easily be able to make subtle changes in it, versus if you just practised it and burned the combinations and hits into your “muscle memory” . The ability to analyse beats will help you be able to specifically mold a beat to any given situation or style of music.

Drum n’ Bass drumming is not…

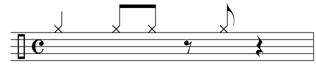

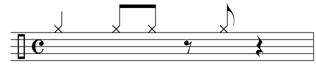

Of monumental importance here is to identify that the following beat is not the type of beat that this book is trying to produce:

In this beat, the left hand remains at the snare playing offbeat 16th notes, while the right hand goes back and forth between accented hi hat hits and accented snare hits. This type of beat is too cluttered with 16th notes and does not give the drummer any more independence or interdependence between the limbs. You also can’t play the hi hat and the snare at the same time. It’s not that this beat isn’t cool, or that it can’t sound great in a certain song, it’s just that this type of beat was created by a drummer, and this book is attempting to bridge the gap between drummers and programmers.

You may find beats where it does sound great to drop your ride limb down to the snare drum. Great! Do it! Just don’t sacrifice the world of possibilities offered by this new style.